Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. To book an appointment with Tom Goom (AKA ‘The Running Physio’) visit our clinic page. We offer both in-person assessments and online consultations.

Running gait retraining research is gathering pace and one of the leaders of the pack is Dr Richard Willy, Assistant Professor at East Carolina University. Richard’s research has found mirror gait retraining to be effective for reducing patellofemoral pain and has highlighted how improving strength doesn’t appear to alter running kinematics. We’re delighted to welcome Richard to the blog and today he joins us to discuss cues for gait retraining. Follow him on Twitter via @RWilly2003 and check out his research profile to see more of his work.

Gait retraining can play an important role in the treatment of many common running injuries, particularly patellofemoral pain, iliotibial band syndrome and tibial stress fractures. Gait retraining is the application of motor learning principles to systematically modify a runner’s gait. While acutely modifying a runner’s gait is easily accomplished, lasting changes in running mechanics can prove more elusive.

Perhaps one of the keys to a successful gait retraining program is viewing running as a coordination skill rather than an aerobic or strength-related activity. The motor control literature suggests that strengthening activates distinctly different areas of the motor cortex than skill training (Jensen 2005). Interestingly, skill training appears to result in cortical re-organization whereas strengthening does not (Remple et al., 2001). Thus, it is not surprising that strength training alone appears inadequate to modify suspect running mechanics in the frontal and transverse plane (Willy and Davis, 2011; Wouters et al., 2012). Gait retraining focuses on altering the skill of running and has demonstrated promise in producing lasting changes in running mechanics.

Words matter

Appropriately shifting a runner’s focus of attention may play a role in the success of gait retraining programs. Attentional focus may come in the form of cues or mode of feedback provided to a runner (Gokeler et al., 2013). With a large degree of consistency in the literature, an external focus appears to enhance motor learning whereas an internal focus is likely detrimental to new skill acquisition (Wulf et al., 2010). An external focus occurs when there is concentration on manipulation of an object external to the body (Wulf, 2007). An external focus promotes greater multi-segmental coordination and promotes a more automatic process (Figure 1) (Wulf et al., 2002). In contrast, instructing a runner to manipulate a body part is considered an internal focus. An internal focus artificially constrains an activity to a specific motor pattern or kinematic strategy (Gokeler et al., 2013). While an internal focus may sound as if the therapist is able to control the movement better, increased muscle co-contraction and decreased coordinative performance result (Zachry et al., 2005). Thus, the use of either verbal cues or feedback with an internal focus may result in an unsustainable increase in metabolic cost and an increase in joint compressive forces due to the muscle co-contraction around a joint.

Cueing lasting changes in running mechanics

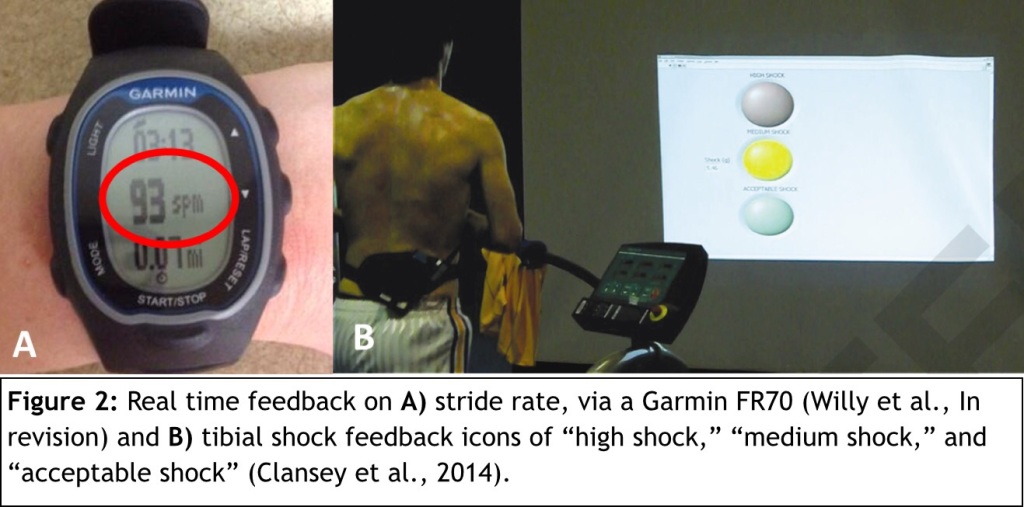

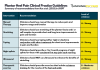

Based on the literature, it appears that an external focus should be used in cueing and feedback to enhance acquisition of a new movement skill. For instance, an increase in step rate or decrease in impact forces during running can be accomplished by meeting a step rate target on a running computer (external focus) (figure 2A) (Willy et al., In revision) or manipulating feedback icons on impact forces (figure 2B)(Clansey et al., 2014), respectively. In contrast, altering step rate or impact forces using the internally focused cue, “land with a more flexed knee” or “land with a midfoot strike” is less effective. The internal focus of “land with a more flexed knee” and “land with a midfoot strike” artificially constrains the runner to that specific kinematic strategy to accomplish the goal of an increased step rate or a reduction in impact forces. The externally focused cueing of “increase your step rate value on the computer” or “reduce your impact forces” allow the runner to find their own unique kinematic solution to the task.

In our recently completed randomized controlled trial, we found that runners utilized a variety of strategies to increase their step rate when they are not constrained to a specific kinematic strategy (Willy et al., In revision). These strategies included various combinations of less knee excursion, landing in less hip flexion, landing in greater knee flexion, less hip extension in terminal stance, landing with a more vertical lower leg, and a flatter footstrike. Interestingly, no single kinematic strategy seemed to be used by all participants. Subject-derived kinematic strategies are also found to be superior in the retraining of walking patterns associated with osteoarthritis of the medial compartment of the knee (van den Noort et al., 2014). As is often pointed out, changing a runner’s mechanics likely shifts the load to other anatomical structures. An external focus allows the runner to spread the increased load across several anatomical structures with the new running pattern and may decrease the risk of a new injury that may occur with gait retraining. By reducing increases in metabolic cost and minimizing the increased risk of injury, a runner may be more likely to adopt the new running pattern in the long term.

Is there a role for internal focus?

Regardless of running experience, some runners have difficulty modifying their gait. These runners can be considered “novice” with the new movement skill and may benefit from a more dynamic feedback system. There is evidence that absolute novices may perform better with an internal focus when learning a new skill (Perkins-Ceccato et al., 2003). Once the novice is able to perform the skill even marginally, a rapid transition to an external focus should be done. For example, the runner in Figure 1a may lack the coordinative ability to activate the gluteus medius to control contralateral pelvic drop. Instructing the runner with the internal focus of “contract your glutes” or “don’t let your hips drop” may prove especially beneficial initially. Once the runner is able to perform the task of controlling contralateral pelvic drop, even marginally, then the cueing and feedback should quickly shift to the external focus described in Figure 1b.

Written by Richard Willy, PT, PhD, OCS, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Physical Therapy, East Carolina University, USA. Follow Richard on Twitter via @rwilly2003

References:

Clansey, A.C., Hanlon, M., Wallace, E.S., Nevill, A., Lake, M.J., 2014. Influence of Tibial Shock Feedback Training on Impact Loading and Running Economy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46, 973-981.

Gokeler, A., Benjaminse, A., Hewett, T.E., Paterno, M.V., Ford, K.R., Otten, E., Myer, G.D., 2013. Feedback techniques to target functional deficits following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: implications for motor control and reduction of second injury risk. Sports medicine 43, 1065-1074.

Perkins-Ceccato, N., Passmore, S.R., Lee, T.D., 2003. Effects of focus of attention depend on golfers’ skill. Journal of sports sciences 21, 593-600.

Remple, M.S., Bruneau, R.M., VandenBerg, P.M., Goertzen, C., Kleim, J.A., 2001. Sensitivity of cortical movement representations to motor experience: evidence that skill learning but not strength training induces cortical reorganization. Behav Brain Res 123, 133-141.

van den Noort, J.C., Steenbrink, F., Roeles, S., Harlaar, J., 2014. Real-time visual feedback for gait retraining: toward application in knee osteoarthritis. Med Biol Eng Comput.

Willy, R.W., Buchenic, L., Rogacki, K., Ackerman, J., Schmidt, A., Willson, J., In revision. In-field gait retraining and mobile monitoring to address running biomechanics associated with tibial stress fracture. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports.

Willy, R.W., Davis, I.S., 2011. The effect of a hip-strengthening program on mechanics during running and during a single-leg squat. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 41, 625-632.

Wouters, I., Almonroeder, T., Dejarlais, B., Laack, A., Willson, J.D., Kernozek, T.W., 2012. Effects of a movement training program on hip and knee joint frontal plane running mechanics. Int J Sports Phys Ther 7, 637-646.

Wulf, G., 2007. Attentional focus and motor learning: A review of 10 years of research. Bewegung und Training 2007, 1-11.

Wulf, G., McConnel, N., Gartner, M., Schwarz, A., 2002. Enhancing the learning of sport skills through external-focus feedback. J Mot Behav 34, 171-182.

Wulf, G., Shea, C., Lewthwaite, R., 2010. Motor skill learning and performance: a review of influential factors. Med Educ 44, 75-84.

Zachry, T., Wulf, G., Mercer, J., Bezodis, N., 2005. Increased movement accuracy and reduced EMG activity as the result of adopting an external focus of attention. Brain Res Bull 67, 304-309.

Love this article. Thank you! Can you share a list of external cues that may be beneficial and the corresponding internal cues to stay away from?

Taylor:

I’ll provide some examples of internal cues and then the alternative external cues for a couple of various gait modifications:

1. Medial collapse mechanics- internally focus on increasing distance between knees, rotate knee forward, keep pelvis from dropping. The alternative external cue: place a marker on the outside of the knees and focus on “push the markers toward the walls”(the runner in the figure at the very top of the article is doing this) or the example in the article for Figure 1.

2. Crossover running mechanics- internal cue: “increase your step width.” External cue: place a piece of tape lengthwise on the front of a treadmill and run straddling it. Option 2: straddle 2 lanes on a running track.

3. Running with reduced trunk control (slouching forward or leaning backward)- internal cue: “don’t let your ribs flare,” “stand tall,” etc. External cue: “lift the ceiling.”

4. Wish to increase hip extension- internal cue: “extend your hip behind you.” External cue: “push the road back.”

5. Wish to reduce impact forces- Internal cue: “land softer,” “flex your knees more,” land on your toes.” “Land with your foot closer to you.” External cue: “reduce the sound (of your impacts).”

These are just a few examples that use the concepts described in the article. These are by no means all-inclusive and are just a few of many possible modifications. Hope this helps. -Rich

Any suggestions for low tech external cues?

Comments are closed.