Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. To book an appointment with Tom Goom (AKA ‘The Running Physio’) visit our clinic page. We offer both in-person assessments and online consultations.

The core of rehab for tendinopathy is building the load capacity of the muscle and tendon through strength work. It’s the area of exercise prescription that has the most support from the evidence, although it should be noted there remains a paucity of high quality research. Beyond strength exercises there is little guidance from the literature in terms of rehab progression. Broadly speaking our goal is to improve the tendon’s ability to handle its functional requirements during everyday life and sport. While doing this we also want to maintain long term tendon health. This article discusses progressing rehab to include more functional exercises to achieve these goals. It is largely theoretical but is based on principles of strength and conditioning and tendon function.

Before reading this I recommend you read part 1 – reducing pain and building strength. To summarise the article; tendon rehab was broken down into 6 phases, phase 1 and 2 were discussed in the first piece. Phase 1 aims to decrease pain by reducing aggravating factors and using midrange isometric exercises and phase 2 aims to strengthen using progressively heavier loads.

For many athletes reducing pain and building strength combined with a gradual return to running will be enough to rehab a tendinopathy. If this is combined with ongoing strength work to maintain tendon load capacity and a sensible training schedule then risk of recurrence will be fairly low. However for some with more severe or persistent tendinopathy or those whose sport requires a high level of loading then progression through the phases to including functional rehab is recommended…and this is where phase 3 comes in…

Transition from phase 2 to 3

Your Physio/ health professional will guide you on rehab progression. Prior to starting functional rehab you need to ensure pain is well managed and you’ve built adequate basic strength. As a rough guide 10 rep max should be equal left and right for the muscle involved.

Phase 3 – Functional Rehab

Below is a picture of Richard Ashton (@c3044700) running the Tour de Helvellyn. Have a look at the terrain he’s running on, the incline, and running surface. Notice he wears a backpack (additional load) and check his position. Like most runners tackling a hill Richard is leaning forward from the trunk and is likely to flex more from the hip than someone running on the flat. Now consider too that this is a 38 mile race tackling 7000ft of ascent! Have to wonder how is he still smiling?!

My point here is that for Richard, and every athlete, there will be a specific amount and type of load the tissues will have to cope with. On this race he will need good ankle dorsiflexion range (upward movement) to cope with the incline and enough strength in this dorsiflexed position to push on with each stride. He’ll need multi-directional ankle stability to conquer those big rocks. Running uphill usually involves more trunk and hip flexion than running on the flat and will require hip extension strength in that flexed position. On top of all this he’ll need strength combined with endurance to keep going over the 38 miles that took him an impressive 7 hours 20 to complete.

Consider that when we run it’s estimated that our body manages a load of roughly 2.5 times our body weight with each stride. We take roughly 500 strides with each leg per mile. Imagine this then over 38 miles, 19,000 strides per leg. If Richard weighs around 80kg that equates to 1.5 million kg of force to manage. If his backpack weights 5kg you can add a further 95,000kg to that load! Luckily tendons have viscoelastic properties that allow them to manage tensile load like this but they do have their limits. Richard is testing these limits – 3 months after Tour de Helvellyn he ran the 103 mile Thames Path Ultra!

When you are building functional strength then you have to consider what activities you’re working toward and adapt the functional strength and conditioning to suit.

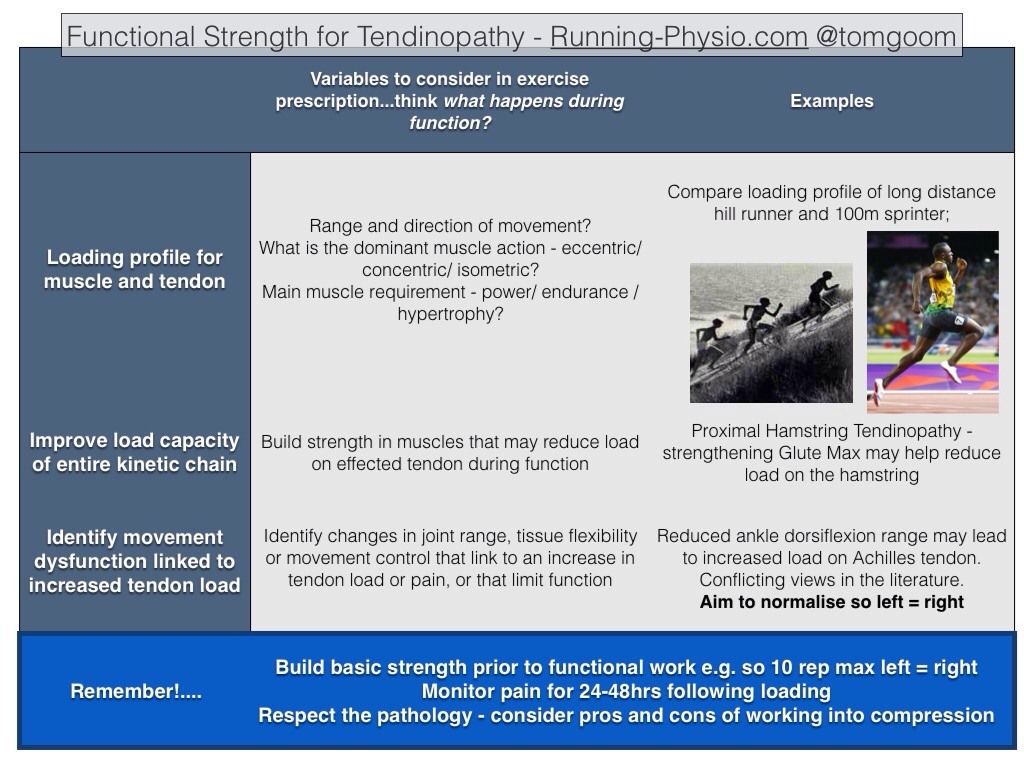

It can help to think of functional rehab in 3 broad categories – exercise specific to the functional requirements of the effected muscle and tendon, improving the load capacity of the entire ‘kinetic chain’, and addressing movement dysfunction that links to the tendinopathy;

If we use Richard as an example how could we adapt his functional rehab to suit his loading profile?

Functional rehab for muscle and tendon

If Richard had a mid-portion achilles tendinopathy his functional strength work could be focused closer to end of range dorsiflexion where he works a lot in hill running. He could do this using a combined approach working multiple parts of muscle function. This could involve exercising concentrically and eccentrically on a step with additional load but just working end of range dorsiflexion to neutral. He could work isometrically – using a leg press, rapidly shifting the weight from one foot to the other but maintaining the ankle in a position close to functional range. He could think more broadly in terms of muscle function and change reps, sets and load to suit strength-endurance. This often involves reducing the load somewhat and increasing reps. For muscle endurance the ACSM (2009) guidelines recommend working with low to moderate weights (40-60% of 1RM) using high reps (>15) and relatively short rest periods (<90 secs). An example programme would be 4 sets of 15-20 reps with a 1 minute rest period (using sufficient weight that you reach fatigue at the end of each set).

Strengthening the entire kinetic chain

By ‘kinetic chain’ we mean the rest of the body that’s involved in a function, we don’t run using one isolated muscle group, the force is distrusted throughout the legs and trunk. If we strengthen other muscles involved in this process we should, in theory, be able to reduce some of the load on the effected muscle and tendon. In doing so we can also improve running economy and performance.

In Richard’s case, strengthening his kinetic chain could involve a number of muscle groups which could help to manage load on the achilles. Running uphill uses the glute max and hamstring muscles to extend the hip from a flexed position and drive on up the hill. Glute med is involved too, stabilising the pelvis and preventing excess hip adduction which can lead to increase load further down the chain. Azevedo et al. (2009) found reductions in the amplitude of gluteus medius and rectus femoris activation shortly before or after heel strike in runners with achilles tendinopathy.

One functional exercise to work on glute max and med would be a high step up with a weighted backpack. Reiman et al. (2012) completed a systematic review of exercises for glute max and med and found the step up achieved the highest glute max activation (74% of Maximal Voluntary Isometric Contraction – MVIC) and moderate glute med activation (44% of MVIC). This exercise could be done on the edge of the step to allow the ankle to dorsiflex to functional range during a step up. Alternatively this could also be done using a steep slope to fully replicate function.

What comes up must come down!…so we should consider too exercises aimed to help descending a hill when running too. This could include eccentric work for the quads, such single leg squats, perhaps on a decline board to simulate the slope. This links with the Azevedo work mentioned above that found reduced rectus femoris activation in runners with achilles tendinopathy.

In addition to strengthening around the hip and knee Richard may also benefit from working more local muscles around the ankle to improve stability over uneven terrain. Strengthening Tibialis Posterior could be beneficial – it is thought to provide 20-30% of the support for the medial arch of the foot (Wearing 2006) and provides dynamic stabilisation of the medial side of the ankle and hindfoot (Ribbans and Garde 2013). Tibialis Posterior also has an important role in ankle plantarflexion. Kulig (2004) noted that it ‘locks’ the transverse joints creating a rigid foot which contributes to the normal heel rise. This is part of the reason why patients are often unable to perform a single leg calf raise following rupture of Tibialis Posterior.

It should be noted that while there is theoretical evidence suggesting a benefit from functional rehab that is no quality evidence that I’m aware of that proves its clinical effectiveness.

Addressing movement dysfunction

Movement dysfunction is a complex area in running and in tendinopathy. It covers a number of factors including strength, joint range of movement, tissue flexibility, movement control and biomechanics. There is a huge amount of variety in what is ‘normal’ and some debate about what aspects of movement we should change or even if we can actually change some of these aspects.

In runners it is often a case of how much you’re running that is relevant to injury rather than your specific running technique. In a recent study by Nielsen et al. (2013) all of the runners in their research that were injured during training had a significant increase in mileage the week prior to their injury. Lun et al (2004) found no connection between static biomechanical lower limb alignment and injury in runners (with the exception of patellofemoral pain). Load is such a key area in development of tendinopathy it is perhaps more likely that it is extrinsic factors such as training volume and intensity that are more relevant than intrinsic factors such as biomechanics. However, as repeated many times before in this series, there is no recipe and rehab must always be specific to the individual.

“Training errors have been reported to be involved in 60% to 80% of runners who have tendon overuse injuries. The most common errors include running a distance that is too long, running at an intensity that is too high, increasing distance too greatly or intensity too rapidly, and performing too much uphill or downhill work.” Paavola et al. (2002)

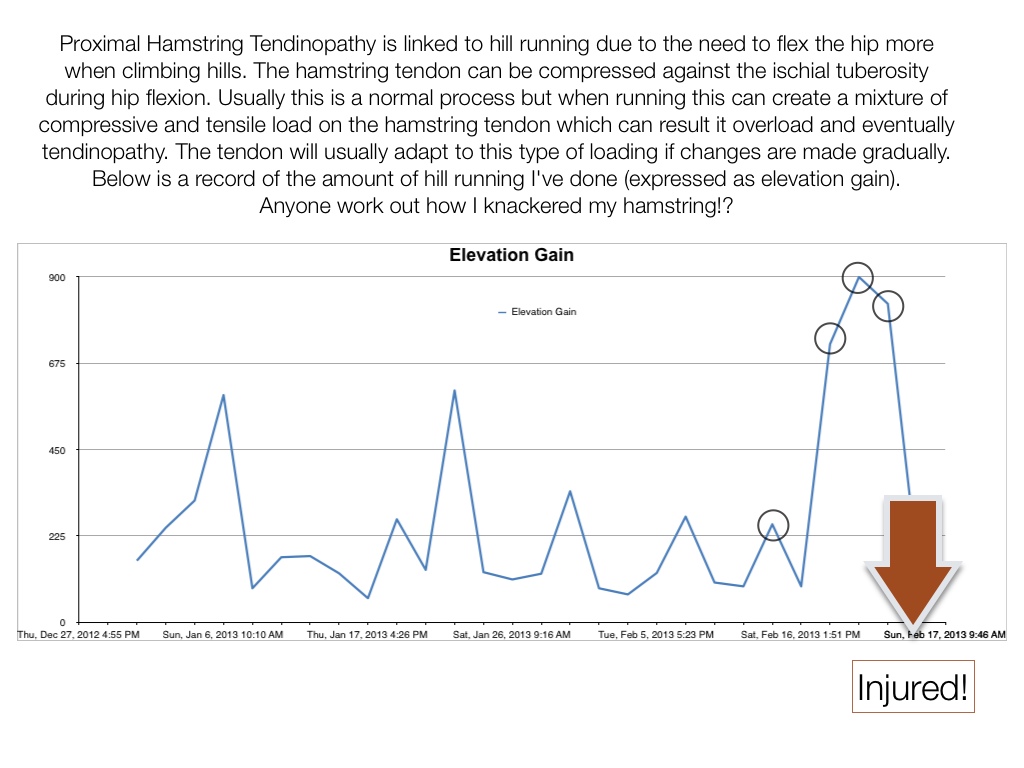

Consider my case of Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy, what is more relevant…

Tightness in my hip flexors leading to excessive load on the hamstring when running;

Or a significant increase in hill running on the Downs because the weather was nice!?

Examining the literature for tendinopathy there are few clear movement dysfunctions that have been demonstrated to be consistently linked with pathology. Impaired control of movement with excess hip adduction during running has been linked to gluteal tendinopathy due to a combination of compressive and tensile load. Again, much of this is theoretical, a combination of work by Grimaldi (2011) on lateral stability of the pelvis and Cook and Purdam (2012) on the role of compression in tendinopathy. Reduced flexibility in quadriceps and hamstring muscles (Witrouv et al. 2001) and decreased ankle dorsiflexion have been associated with patellar tendinopathy (Malliaras et al. 2006)

Achilles tendinopathy and movement dysfunction in runners has been more extensively researched. Munteanu and Barton (2011) conducted a systematic review of literature on this topic and concluded,

“Those with Achilles tendinopathy have increased eversion range of motion of the rearfoot, reduced maximum lower leg abduction, reduced ankle joint dorsiflexion velocity and reduced knee flexion during gait. Those with Achilles tendinopathy also displayed altered plantar pressures and ground reaction forces and showed a reduced peak tibial external rotation moment.”

They also urged caution when interpreting these findings due to the limited quality of a number of the studies included. There are also some conflicting views to consider – Kvist et al. (1991) and Kaufman et al. (1999) both found achilles tendinopathy to be associated with decreased ankle dorsiflexion while Mahieu et al. (2006) found it was linked to increased dorsiflexion range.

So where does this leave us when rehabbing movement dysfunction? Like many aspects of patient care it comes down to assessing the individual and reasoning how each factor is linked and what is key. In terms of movement dysfunction look for differences between the symptomatic and asymptomatic side and see if they link with the pathology. Also aim to restore enough range and control of movement for function.

From available evidence it appears that restoring ankle dorsiflexion is important in both achilles and patellar tendinopathy. Improving single leg balance and single knee dip control are good starting points for movement control before progressing to more dynamic exercises. Muscle flexibility may be linked to tendinopathy but use caution with stretches, especially with insertional tendinopathy, as these can aggravate symptoms. The use of foam rollers or massage has been suggested as an alternative to improve flexibility but is not evidence based.

One final question…

…If we really want to replicate function why not just run?!

Silbernagel et al. (2007) demonstrated that there are specific benefits associated with continuing sport as part of your rehab as long as pain is closely monitored. Running is likely to have benefits on cardiovascular fitness but is less likely to be as effective in building strength or improving tendon load capacity. In addition running activates the tendon’s Stretch-Shortening-Cycle which requires adequate muscle strength to avoid excessive load on the tendon.

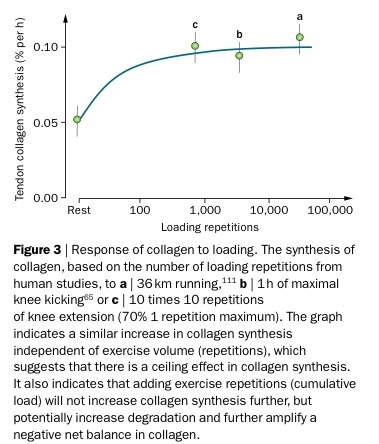

The difference between functional rehab and just running comes down to the type of loading and how the muscle and tendon respond to it. The table above (reproduced from Magnusson et al. 2010 freely available online here) shows that tendon collagen synthesis is similar when comparing a 36km run and 10 times 10 reps of knee extension at 70% 1RM. Consider that for a moment, running over 20 miles only achieves roughly the same collagen synthesis as 100 reps of an exercise but a) has more potential to aggravate the pain and b) is less likely to result in significant muscle strength changes.

A graded return to running is a valuable part of tendon rehab but it isn’t a replacement for appropriate strength work.

Summary of functional rehab for tendinopathy: functional rehab can be a complex area and requires the assessment and advice of a Physio/ health professional. Exercises should be designed to improve the load capacity of the effected tendon and muscle during function as well as the rest of the kinetic chain. Identifying relevant movement dysfunction can be challenging but should involve assessment of joint range of movement, tissue flexibility, control of movement and biomechanics. These areas should be addressed while respecting the pathology involved and monitoring pain in response to loading. Exercises in positions with tendon compression should be use with caution.

Coming up in part 3 – returning running and the role of training error in tendinopathy

And finally…

A special thanks to Richard Ashton for letting me use his picture and his heroic running as an example for this article. Give that man a follow!…. @c3044700