Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. For more information see our Terms and Conditions.

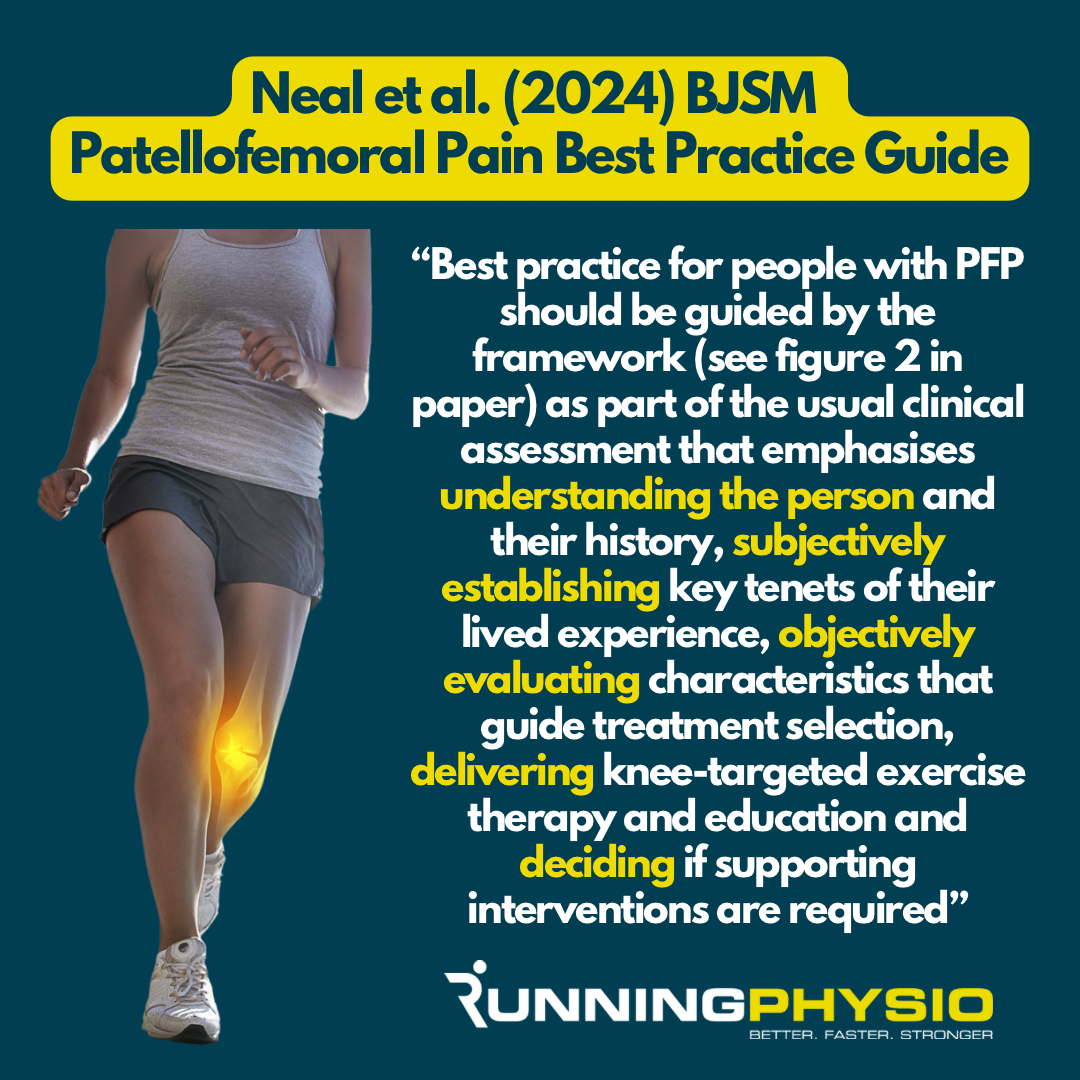

High quality research, clinical expertise and patient involvement are 3 key components of evidence-based care. A new paper from Neal et al. (2024) has combined all 3 to produce a Best Practice Guide (BPG) for Patellofemoral Pain (PFP).

This is an exceptional piece of work that I recommend reading in full. It’s applicable to most patients with PFP (not just athletes). In today’s newsletter I’ll summarise the key points and explore how we can apply them for runners with PFP.

Neal et al. (2024) describe a framework which centres around 4 broad areas:

-

- Understanding the person and their history

- Subjective assessment of why a person has sought treatment and what factors are having the greatest effects on their symptoms

- Objective assessment of physical impairments

- Delivery of care and deciding on supporting interventions.

Education is considered key and should ‘underpin all interventions’. Knee targeted exercises are recommended and may be accompanied by hip targeted exercises.

Foot orthoses, manual therapy, movement/ running retraining and taping were considered ‘supporting interventions’ which can be included and adapted based on the patient.

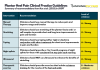

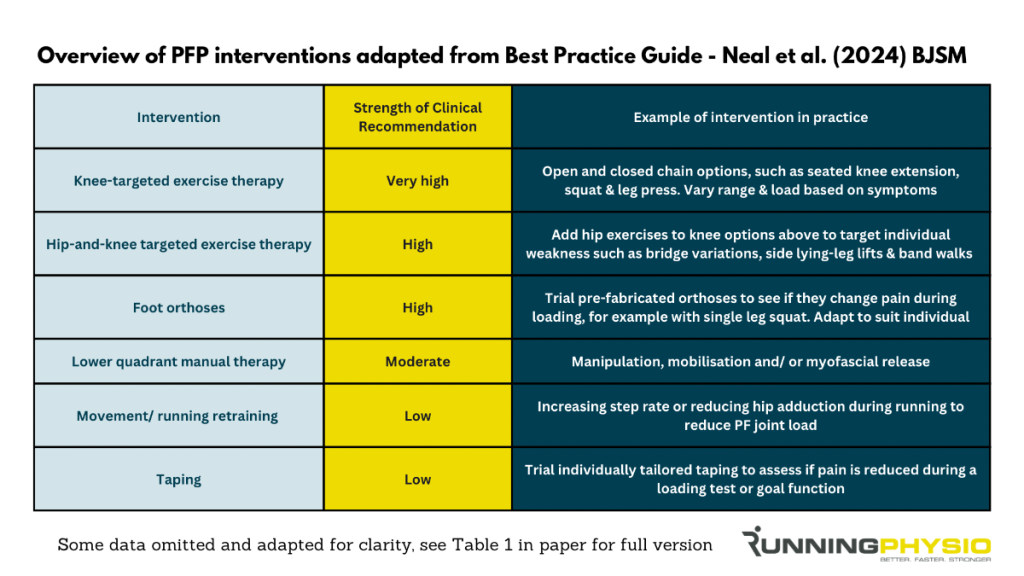

Here’s a summary of some of the interventions that are discussed in the BPG. For clarity we have removed some interventions that were not recommended or are not commonly available in clinic so I’d recommend seeing the full table in the paper for more information (Neal et al. (2024) Table 1).

Let’s consider how we might apply this guidance for a runner with PFP.

Understanding the person and their history

I think in general when helping someone with an injury the better you know them as a person, the better results you get!

That takes time and it starts with listening to their story. What was the history? How did it start? Were there any changes in training? PFP has been associated with increased running volume (Nielsen et al. 2013) and we’d also expect downhill running to increase knee load (Van Hooren et al. 2024)

It’s vital to discuss pain behaviour and beliefs. What does the patient believe is happening to their knee? Do they see running/ activity as damaging?

Look for aggravating movements that can be adapted or targets for load management. Try to establish what is manageable for them at present in terms of activity – this can be the starting point when building back.

Subjective assessment

Asking the right questions and exploring the answers is vital for a successful subjective assessment.

Why have they sought care?

What is the biggest issue at present? Is there something they are especially worried or distressed about?

What are their goals?

Their answers are instrumental to plan treatment and guide return to function.

We may ask about mood and mental well-being. Neal et al. (2024) mention that “People with PFP are six times more likely to be anxious or depressed” citing a study by Wride and Bannigan (2019).

It may be appropriate to refer to a Mental Health Professional and there is some evidence that mindfulness can improve outcomes in runners with PFP. It can also be valuable to assess a patient’s psychological response to pain and injury using a Pain Catastrophising Scale.

Objective assessment

Key objective tests for runners with PFP include strength, movement patterns and pain provocation tests.

For strength testing I would prioritise the quads (open and closed chain) and glutes but also consider hamstring and calf strength. We need to consider symptoms during testing and may need to allow symptoms to settle before more challenging tests can be completed.

Movement patterns such as single leg squat and provocative movements such stair ascent/ descent can be assessed with the aim to see if the patient may be placing more load on the PF joint during these tasks. Reducing hip adduction and/ or knee flexion may help reduce PF load and help symptoms.

We should be mindful though that these can also be used as an avoidance strategy, for example post ACL reconstruction it’s common for runners to significantly reduce knee flexion during the stance phase which we’d aim to address when symptoms allow.

Single leg squat (or other symptomatic movements) can also be used as a pain provocation test with the runner scoring the pain out of 10. This allows us to monitor improvement and assess the effectiveness of treatment. For example, scoring pain during stair descent then repeating the test with orthoses in-situ or taping to see if symptoms improve.

Deciding and delivering care

We always want to support a patient’s autonomy so treatment should be decided with a patient rather than for them!

The BPG recommends knee-targeted exercise therapy and hip exercises should also be considered. Symptom severity and irritability will influence exercise selection and those who are unable to tolerate loaded knee flexion may benefit from a greater focus on hip strengthening initially. As symptoms improve they can then often target the knee more and modify range and load to find a manageable level.

We know from previous work that education and load management are vital for PFP in runners:

Gait analysis and retraining can also be considered for runners with PFP. Addressing over-striding or reducing excessive hip adduction can help with symptoms during running.

I’m currently working on some new videos for you which will delve into management of patellofemoral pain in more detail, including how we apply the key strategies in practice. I’ll let you know as soon as they’re available!