Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. To book an appointment with Tom Goom (AKA ‘The Running Physio’) visit our clinic page. We offer both in-person assessments and online consultations.

Physiotherapist, Pain Specialist and seriously quick runner Derek Griffin joins us again today to talk about exposure therapy for runners and how we can apply its principles to rehab and gait retraining. Derek’s previous post on why runners have pain has been very popular and he played a key role in developing our Tendon Health Questionnaire (#TendonQ). You can also find Derek’s work in national press; he co-wrote a fantastic article on low back pain in the Irish Independent.

Follow Derek on Twitter via @DerekGriffin86

1. Tissue tolerance, nociception & pain

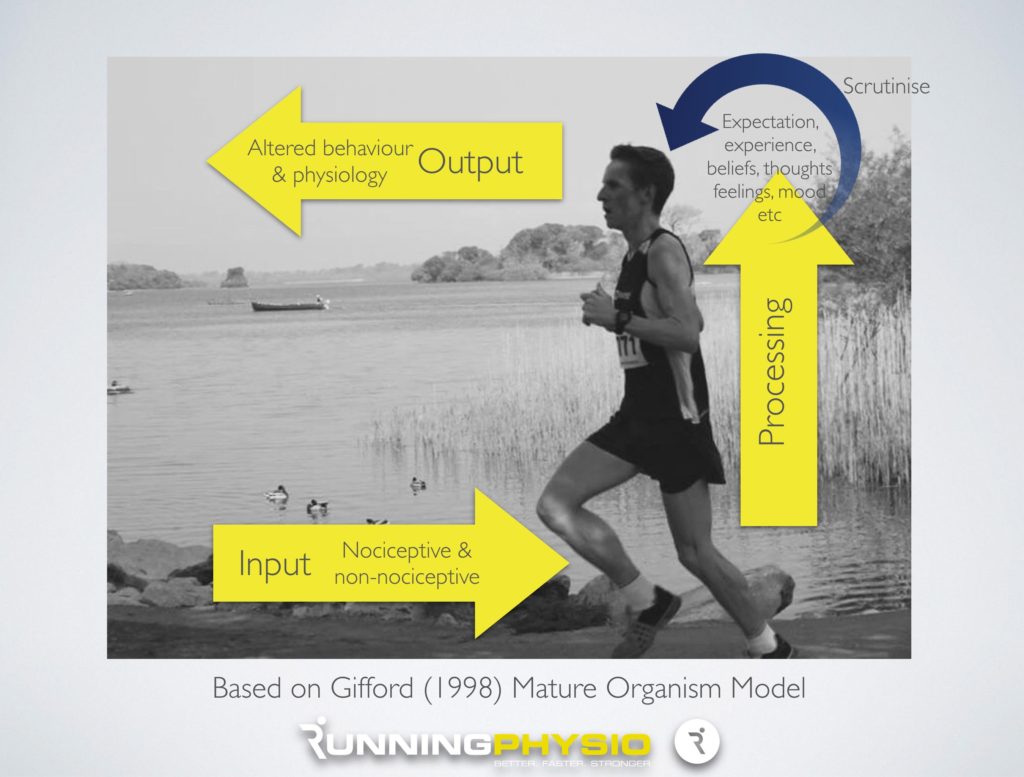

Running remains one of the most popular forms of physical activity globally and its health-enhancing effects have been well documented. Although variable across studies, the prevalence of running-related injury and pain appears high. “Overuse” injury is common in running populations whereby pain onset is insidious, gradually becomes more noticeable over time and is most often not attributable to a specific incident or trauma. A model emphasising tissue or structural change remains the dominant model used to explain pain in runners. Undoubtedly, tissue changes in response to load are important considerations. Recent evidence supports training errors (Gabbett, in press) as well as biomechanical variables (Napier et al. 2015) as potential risk factors for injury or pain in athletes. Put simply, where the loading demands placed on a tissue exceeds the tissue’s tolerance to load, peripheral sensitization may ensue (Cook and Docking, in press). However, the experience of pain and its impact on function in athletic populations is complex with recent evidence suggesting that psychosocial factors, in addition to physical factors and biomechanics, play an important role (Cahalan et al. 2016). This has important implications for both the assessment and treatment of runners with pain.

2. Associative learning & non-nociceptive cues: Clinical implications

In recent years, there has been a welcome increase in the number of studies published investigating interventions to treat common running-related “injuries” including patellofemoral pain, lateral knee pain and exertional lower leg pain. The emphasis is placed on i) load modification (training modification and/or gait retraining) (Barton et al. 2016; Neal et al. 2016) and ii) interventions to increase tissue tolerance (strength & conditioning programmes) (Bazyler et al. 2016). Such interventions have a strong theoretical rationale and there is emerging evidence supporting that they are effective at reducing pain at least in the short term (Barton et al. 2016). The obvious focus of such interventions is on optimising musculoskeletal structures to cope with the loading demands of running. However, while peripheral nociception is commonly involved in such pain presentations, the role of non-nociceptive pain mechanisms in the experience of pain has recently attracted more attention (Moseley & Vlaeyen, 2015) and warrants more consideration in the treatment of athletes with pain (Wallwork et al, in press).

The concept of associative learning and its role in pain perception has implications for how we design interventions to treat athletes with pain. Nociception is never an isolated event. Nociception (which signals potential danger) is also accompanied by non-nociceptive sensory stimuli (e.g.visual, auditory, proprioceptive etc.). It is proposed that when nociceptive and non-nociceptive stimuli are repeatedly paired together, then it is plausible that the non-nociceptive stimuli begin to “predict” danger and may be involved in the experience of pain (for a comprehensive overview see Moseley & Vlaeyen 2015). The idea that pain can be classically conditioned has some empirical support (Madden et al. in press). Furthermore there is emerging evidence that manipulating these non-nociceptive stimuli can change the pain experience (Harvie et al. in press). Running is a highly repetitive activity and therefore this greatly enhances the potential for associative learning. So is it possible that factors such as who you are running with, where you are running, the speed you are running at, your perception of effort, your thought processes, your attentional focus, your position in the gait cycle could come to elicit pain merely by their association with nociceptive activity (either ongoing or in the past)? Could this partly explain the high recurrence rate of running-related injuries? Can we design our interventions to account for associative learning? The answers to these questions are currently unknown but warrant consideration.

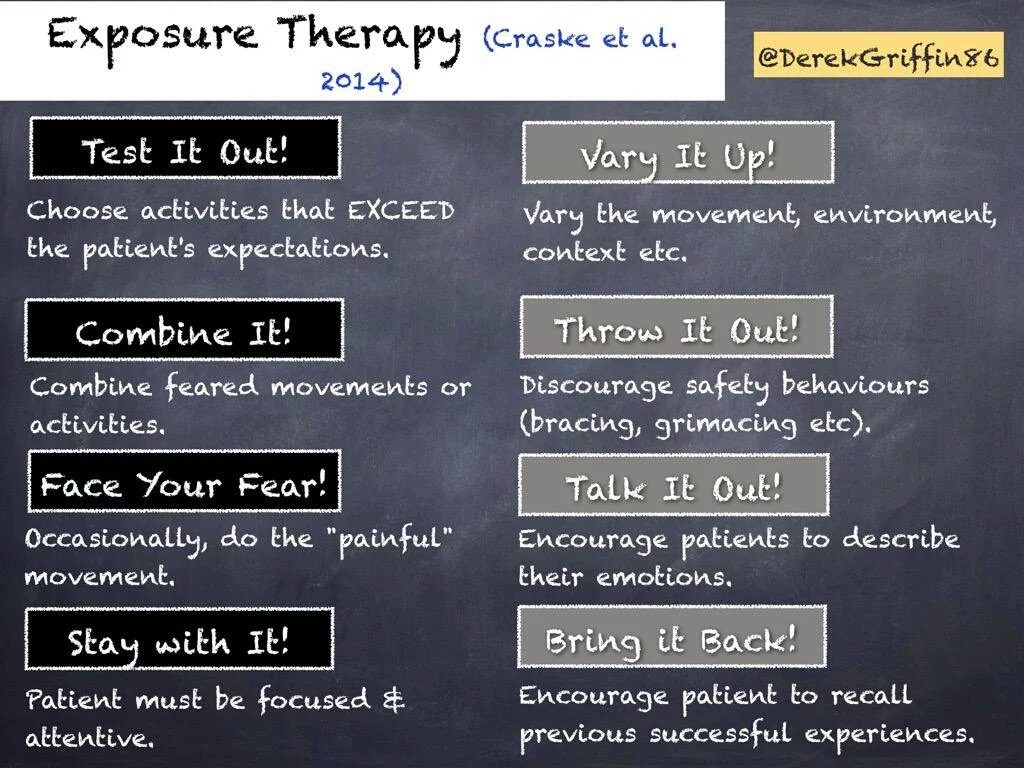

3. Exposure-based interventions

Given the potential for the involvement of non-nociceptive mechanisms in pain, our interventions should aim to also address this. Exposure therapy is a widely used intervention in the treatment of pain. It aims to dissociate contextual cues from potential threat (Craske et al. 2014; Harvie et al. 2016). It is highly context specific and learning is optimised when a number of principles are adhered to (Craske et al. 2014). While current, commonly used interventions for treating runners with pain (gait training, strength & conditioning etc.) are useful in addressing nociceptive processes, they may not fully address potential non-nociceptive pain mechanisms. This is not to say that such interventions are not important. Instead they should be seen as complimentary to a running-based exposure intervention. The final section will offer some practical insight into how these non-nociceptive influences on pain may be addressed (based on principles outlined by Craske et al. 2014). These insights are only speculative at present but will hopefully stimulate discussion around this important topic.

4. Design of exposure-based interventions: Practical suggestions

Violation of Expectation:

What is it? Learning is optimised if what the patient actually experiences is different from what they expected (i.e. “prediction error”) (Brown et al, in press; Fernandez et al, in press).

Treatment Implications; Prior to an intervention, take care not to bias patients’ expectations through verbal suggestion on what the likely outcome will be. Learning is best if it is implicit. For example, if you decide that an individual with knee pain would benefit from an increase in their cadence, do not condition them PRIOR to the testing that you suspect that it will result in less pain. Ensure that any reduction in pain comes as a “surprise”.

Variability:

What is it? Variability refers to how much the context is varied during the rehabilitation. Pain perception is closely tied to context. (Carlino & Benedetti, in press)

Treatment Implications; Manipulating and varying the context is a very effective way of altering the non-nociceptive cues that may have come to imply danger through their association with nociception. Context can be varied in many ways: running in different environments, at different speeds, on different terrains, with different people, using different shoes, in different mood states etc. Of course, tissue-related factors (strength, endurance etc.) will influence how much you can vary the context but every attempt should be made to do so regularly where possible.

Removal of Safety Behaviours:

What is it? Safety behaviours refer to the “tricks or aids” that individuals may use to assist with an activity. Some believe that they may contribute to sustained threat beliefs which obviously are maladaptive in the long term. Although the removal of safety behaviours is commonly recommended the evidence for the use or non-use of safety behaviours is not strong (Meulders et al. 2016). The consensus is that safety behaviours should be phased out gradually over time (Craske et al. 2104).

Treatment Implications; The nature of safety behaviours used among runners is highly variable. These may include strapping, tape, creams or ointments, supports etc. It is important to discourage use of such strategies as early as possible although it is acknowledged that under some circumstances, such behaviours may assist with activity engagement especially in the short term.

Attentional Focus:

What is it? Learning is enhanced when the patient pays close attention to the behavioural task.

Treatment Implications; Ensure that the runner pays attention to the task at hand and the context in which it is occurring. For example, a runner during gait training could be encouraged to pay attention to their environment, their surroundings, their perception of effort, their body position etc. Strategies that promote body awareness and mindfulness may be helpful in this regard.

Retrieval Cues:

What is it? Retrieval cues act as “reminders” of previously successful attempts of an activity or task (Craske et al. 2014).

Treatment Implications; Retrieval cues can take many formats and can be anything that reminds the runner of a previously successful attempt at running. For example a runner who undertook a gait retraining programme on a running track may be advised to recall this when starting their transition to the road. Visualisation and imagined movement (using a runner’s own past experiences such as running on the track pain-free) is also a helpful strategy in this regard. Retrieval cues simply act a reminder of what an individual has learned from previous episodes of exposure.

Affect labelling:

What is it? During exposure, individuals are encouraged to express the emotions that they are feeling. (Niles et al. 2015)

Treatment Implications; For example, during gait retraining, runners may be encouraged to verbalise what they are feeling. What are they feeling? Is their experience different to what the expected? Do they have any concerns? Other strategies include keeping a brief diary to describe their experiences as they progress through their programme.

5. Conclusion

Pain in runners is complex. It is highly likely that both nociceptive and non-nociceptive pain mechanisms are involved. Any well designed intervention programme should reflect this. Exposure-based interventions offer promise in this regard but require further study. Although not the primary focus of this blog post, it must be acknowledged that pain is a multidimensional experience that is also influenced by a range of factors across multiple domains. Any treatment plan that fails to address the physical, lifestyle, cognitive, social, psychological, personal or neurophysiological factors that are known to influence pain should be considered incomplete and this is not different among athletic populations. Research in this regard among runners is currently lacking and should be prioritised going forward. Biomedical models of care still dominant the treatment of pain in sporting populations. A shift from a purely biomechanical understanding of pain in runners to a neuro-scientific understanding will undoubtedly be a worthwhile development.

6. References

Barton, C.J., Bonanno, D.R., Carr, J., Neal, B.S., Malliaras, P., Franklyn-Miller, A. and Menz, H.B., (2016). “Running retraining to treat lower limb injuries: a mixed-methods study of current evidence synthesised with expert opinion.” British journal of sports medicine, 50(9), pp.513-526.

Bazyler, C.D., Abbott, H.A., Bellon, C.R., Taber, C.B. and Stone, M.H., (2015). “Strength training for endurance athletes: Theory to practice.” Strength & Conditioning Journal, 37(2), pp.1-12.

Brown, L.A., LeBeau, R.T., Yi Chat, K. and Craske, M.G., (in press). Associative learning versus fear habituation as predictors of long-term extinction retention.” Cognition and emotion, in press.

Cahalan, R., O’Sullivan, P., Purtill, H., Bargary, N., Ni Bhriain, O. and O’Sullivan, K., (2016). “Inability to perform because of pain/injury in elite adult Irish dance: A prospective investigation of contributing factors.” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 26(6), pp 694-702.

Carlino, E. and Benedetti, F., (in press). “Different contexts, different pains, different experiences.” Neuroscience, in press.

Cook, J.L. and Docking, S.I., (in press). “Rehabilitation will increase the ‘capacity’of your… insert musculoskeletal tissue here….” Defining ‘tissue capacity’: a core concept for clinicians. British journal of sports medicine, in press.

Craske, M.G., Treanor, M., Conway, C.C., Zbozinek, T. and Vervliet, B., (2014). “Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach.” Behaviour research and therapy, 58, pp.10-23.

Fernández, R.S., Boccia, M.M. and Pedreira, M.E., (in press). “The fate of memory: Reconsolidation and the case of Prediction Error.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, in press.

Gabbett, T.J., (in press). “The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?.” British journal of sports medicine, in press.

Harvie, D.S., Broecker, M., Smith, R.T., Meulders, A., Madden, V.J. and Moseley, G.L., (in press). Bogus visual feedback alters onset of movement-evoked pain in people with neck pain. Psychological science, in press.

Harvie, D.S., Meulders, A., Madden, V.J., Hillier, S.L., Peto, D.K., Brinkworth, R. and Moseley, G.L., (2016). “When touch predicts pain: predictive tactile cues modulate perceived intensity of painful stimulation independent of expectancy.” Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 11, pp.11-18.

Madden, V.J., Harvie, D.S., Parker, R., Jensen, K.B., Vlaeyen, J.W., Moseley, G.L. and Stanton, T.R., (in press). “Can Pain or Hyperalgesia Be a Classically Conditioned Response in Humans? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Pain Medicine, in press.

Meulders, A., Van Daele, T., Volders, S. and Vlaeyen, J.W., (2016). “The use of safety-seeking behavior in exposure-based treatments for fear and anxiety: Benefit or burden? A meta-analytic review.” Clinical psychology review, 45, pp.144-156.

Moseley, G.L. and Vlaeyen, J.W., (2015). “Beyond nociception: the imprecision hypothesis of chronic pain.” Pain, 156(1), pp.35-38.

Napier, C., Cochrane, C.K., Taunton, J.E. and Hunt, M.A., (2015). “Gait modifications to change lower extremity gait biomechanics in runners: a systematic review.” British journal of sports medicine, 49(21), pp.1382-1388.

Neal, B.S., Barton, C.J., Gallie, R., O’Halloran, P. and Morrissey, D., (2016). “Runners with patellofemoral pain have altered biomechanics which targeted interventions can modify: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Gait & Posture. 45, pp. 69-82.

Niles, A.N., Craske, M.G., Lieberman, M.D. and Hur, C., (2015). “Affect labeling enhances exposure effectiveness for public speaking anxiety.” Behaviour research and therapy, 68, pp.27-36.

Wallwork, S.B., Bellan, V., Catley, M.J. and Moseley, G.L., (in press). “Neural representations and the cortical body matrix: implications for sports medicine and future directions.” British journal of sports medicine, in press.