Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. To book an appointment with Tom Goom (AKA ‘The Running Physio’) visit our clinic page. We offer both in-person assessments and online consultations.

For a while, we’ve been searching for the right person to tackle the complex issue of meniscus injuries in the knee. As you’ll see from the work below the term ‘torn meniscus’ can cover an awful lot! Luckily for RunningPhysio we found just the right guy….Wouter is a top physio with brilliant knowledge of the literature. He’s been a huge support to RunningPhysio of late and a major contributor to our Physio Resource Page. He’s kindly agreed to take on the meniscus in a two-part blog. You can follow Wouter on Twitter via @Neuromanter

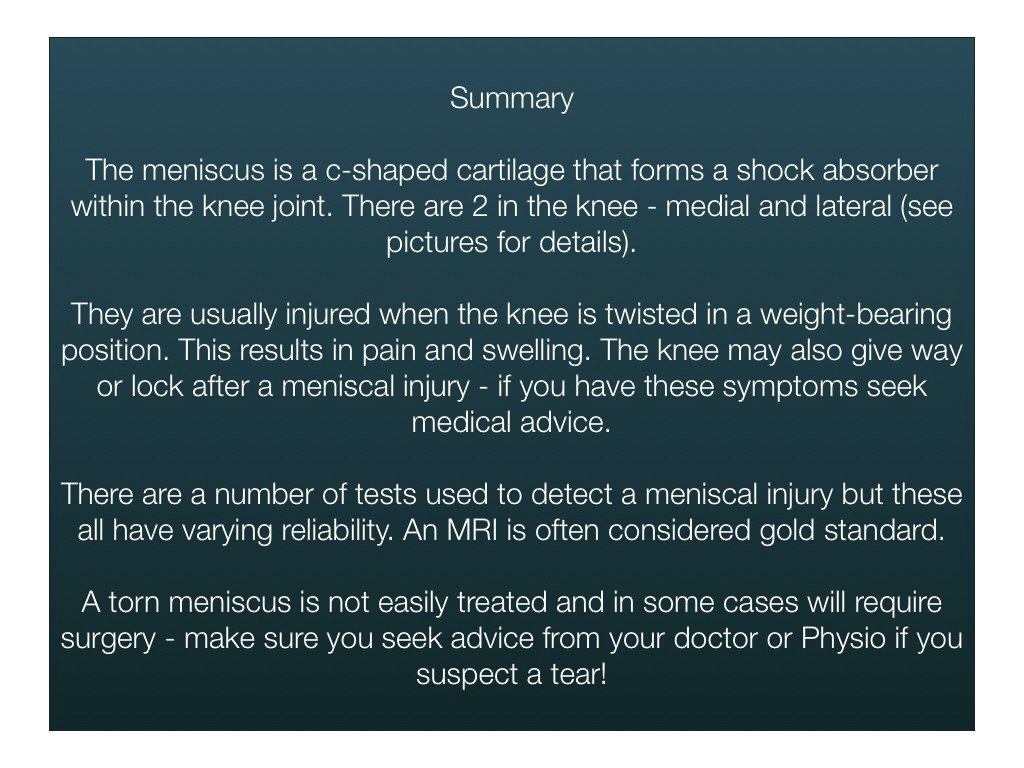

Part 1 looks at what the meniscus is, symptoms of injury and evidence behind diagnosis. It is a technical piece so we’ve included a key point summary at the end!…

….So Twitter can be an interesting way of communication… A time back I signed up, created an account and got to meet interesting and very smart people. Twitter allows us physios to debate and discuss what is going on in the world of physiotherapy. One of the people I met was @tomgoom, we chatted debated and in the end he asked me to write a blog about ‘the meniscus’ (weird c-shaped things you can find in a knee).

So this is it, my maiden trip into blog writing (don’t shoot me if it’s bad).

In physiotherapy, we get a lot of patients with meniscal injuries. It’s a very common cause of knee pain, it keeps people away from work and sports… The goal of this blog is to create some clear answers for people with meniscal tears…

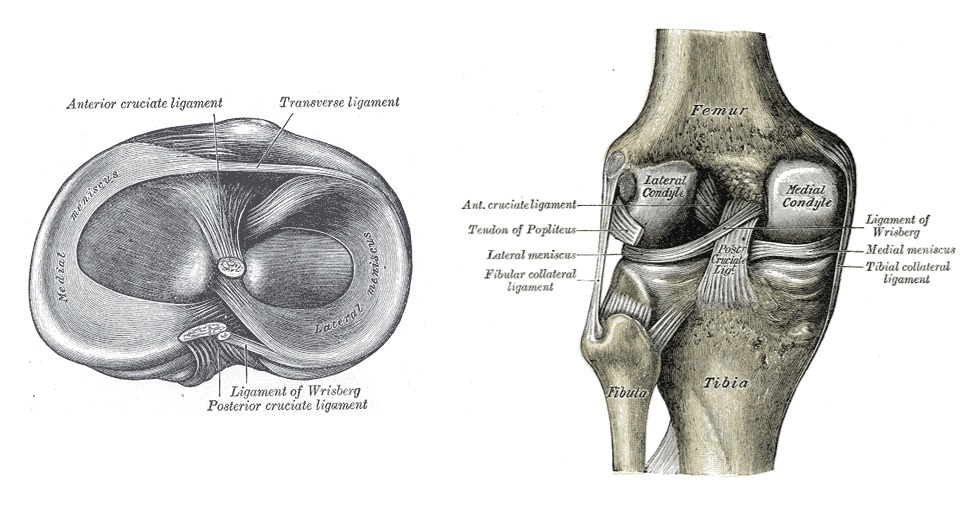

The menisci are c-shaped structures situated within the knee joint between the femur and the tibia;

They are made out of fibrocartilage (75% circumferential type 1 collagen fibres and 25% radial fibres). Their blood supply is good in the most peripheral fibres (that comes down to 20%), the inner ring of the meniscus is avascular (no blood supply) and gets nourished by the synovial fluid, the middle 1/3 of the meniscus is a combination of vascular supply and nourishment through synovial fluid. The menisci play an important role in the knee and have different functions (Bessette G.C., 1992):

- load transmission.

- lubrication of the articular surfaces.

- proprioception.

- providing stability to the knee.

- shock absorption.

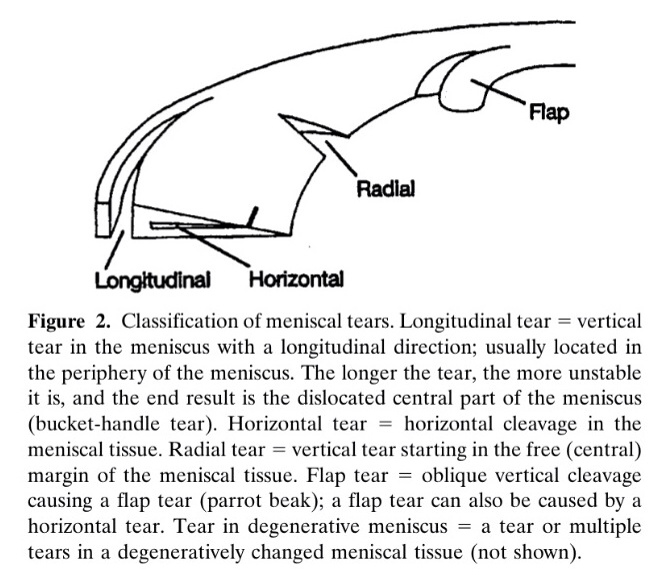

Because of its functions, the meniscus can be vulnerable to injury. There are many different types of meniscal tears, here are the most common:

- Horizontal tear: tear is parallel to the tibial plateau and divides the meniscus in an upper and lower segment (Jee W.H. et al 2003)

- Vertical tear:

- Vertical longitudinal tear: occurs parallel to the long axis of the meniscus, perpendicular to the tibia plateau (Jee W.H. et al 2003).

- Vertical radial tear: These tears result in 2 separate pieces, or a single piece of meniscus still attached to the tibia (Magee T. et al 2002; Tuckman G.A. 1994). These types of tears are usually unrepairable (Harper K.W. et al 2005). Partial-thickness radial tears can be debrided, but will probably not regain full function and may lead to accelerated degenerative changes in the knee (Helms C.A. 2002, Magee T. et al 2002; Tuckman G.A. 1994). As a result a small radial tear can have a significant detrimental effect on the knee and be a cause of pain.

- Complex tear: those types of tears have two or more configurations of tears (Jee W.H. et al 2003)

- Bucket-handle tear: Is the most common type of displaced flap tear occurring in 10 to 26% of patients (Magee T. et al 2004; Dorsay T.A. 2003, Vereridis A.N. et al 2006)

- Free fragments: is very rare, occurring in 0.2% of symptomatic meniscal lesions (Ruff C. et al 1998)

- Flap tear (can be displaced): is a short-segment horizontal tear.

- Root tears: this occurs at the tibial attachment or ‘root’ of the meniscus (only described posterior) (Bordy J.M. et al 2006).

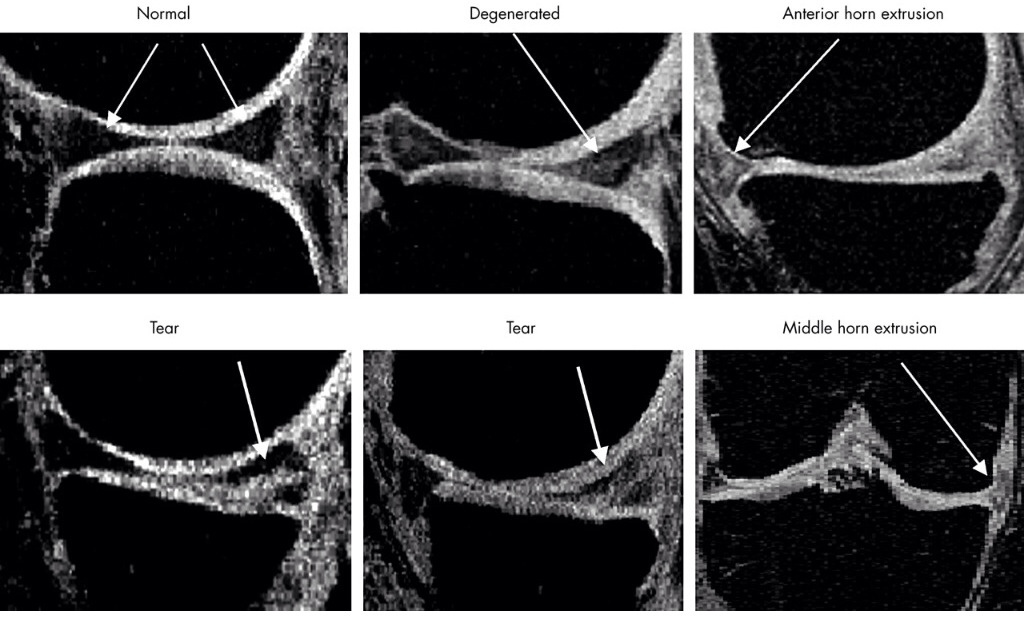

Picture from Englund et al. (2003) freely available online here.

So how do we injure a meniscus?

The cause of a meniscus tear is usually a twisting force with significant torque. A footballer kicking a ball putting his whole weight on one leg onto the meniscus, a ballet dancer twisting his/her knee doing a pirouette, a gardener stepping off a ladder, putting weight on his foot and twisting his knee, etc…

Not only torque is of importance, other injuries in the knee, which cause the femur to slide back and forward on the tibia can result in meniscal tears (e.g. ACL rupture, torn medial or lateral ligaments or degeneration of the meniscus due to arthritic disorders in the knee).

How do you know you’ve torn your meniscus?

There is first of all the signs and symptoms of a meniscus tear (they can vary between type of tear), but to keep it nice and simple, we will put them into 3 categories:

- Small meniscus tear

- you’ll feel slight pain and there will be a little swelling (for 2-3 weeks)

- Moderate tear

- Pain localised on the left or right side of the knee (depending on if it’s the lateral or medial meniscus).

- Progressive swelling over a couple of days (2-3days)

- The knee will feel sensitive and stiff

- There can be difficulty in fully flexing or extending the knee

- Sharp stabbing pain can be felt when twisting the knee

- Usually pain settles within 2-3 weeks.

- Severe tear, all of the symptoms mentioned above plus;

- Popping/clunking or locking sensation in the knee.

- You may have a giving away sensation without warning.

So what do you do if you’re sensing the symptoms described? You need to see a medical professional and get a proper diagnosis. Just to make this clear – sensations of giving way or locking of the knee are not to be ignored – get it checked out!… So what are the most commonly used techniques to diagnose a tear?

- Doctor/physio examination – manual techniques (Mcmurray test, Joint line tenderness test, Apley test, Thessaly test, Ege’s test…

- Ultrasound imaging (US).

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging).

- Diagnostic arthroscopy (surgery).

You can differentiate between invasive (arthroscopy) and non- invasive techniques (manual testing, US, MRI) to test the meniscus for tears. There are a lot of studies in this area so we have chosen a select few to give you an impression of how accurate and reliable these test procedures are.

Manual Testing:

A lot of tests exist to assess if the menisci are ruptured or not. So I dove into the literature to know if any of that stuff is really reliable. As for many techniques used in our profession, research data is mixed. So what about meniscus testing (If you’re an athlete reading this, you might as well skip this section, it’s all about crunching numbers, so it could get a bit boring… not for you physios of course, even if you don’t want to read this, it’s mandatory ;-)).

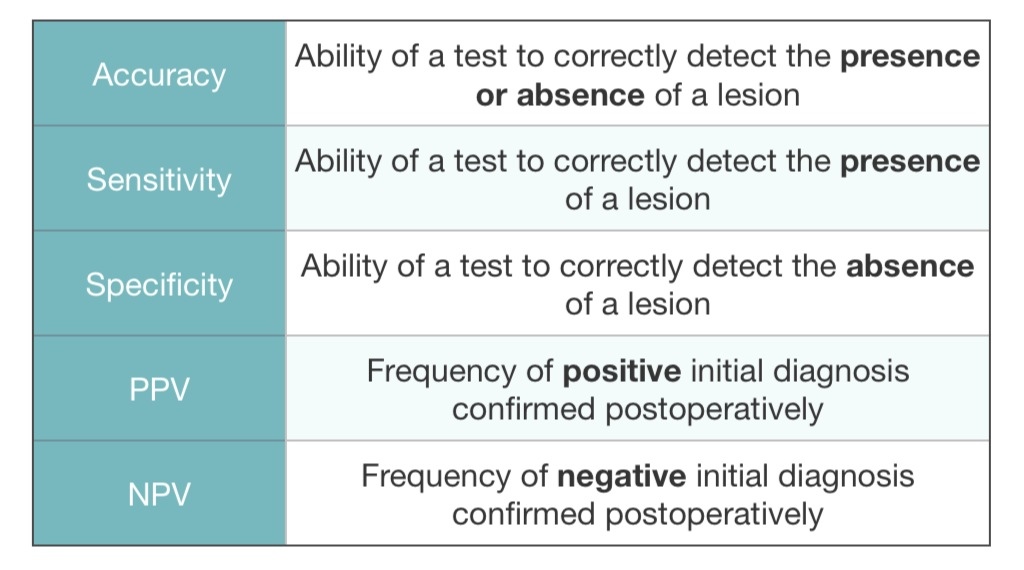

A lot of terms like accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV will return. So let’s clarify those terms:

In a study done by Mohan et al (2007), they tested the effectiveness of the Mcmurray test and Joint line tenderness (JLT) to assess meniscal tears. They verified their results arthroscopically. The clinical diagnosis had an accuracy of 88% for medial meniscal rears (sensitivity 98%, specificity 65%, positive predictive value of 87% and negative predictive value of 93%). For the lateral meniscus, the clinical diagnosis had an accuracy of 92% (sensitivity 91%, specificity 93%, positive predictive value 71% and negative predictive value of 98%). Rose R.E. (2006) tested the accuracy of the joint line tenderness test alone, the test for the lateral meniscus had an accuracy of 93%, a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 93.

A lot of these meniscus tests are all in a non-loaded position (patient is lying supine or prone on the examiners’ table), so fair point to those researchers who went for a modified test in a loaded position (this might mimic the patients’ pain better because they mostly experience pain in a knee loaded position). So in a study by Akseki D. et al (2004), 3 test were studied in their accuracy, sensitivity and specificity compared with the gold standard arthroscopy. The joint line tenderness test, the Mcmurray test and the Ege’s test (loaded position). So there was a good correlation for all 3 tests in detecting a meniscal tear. In this study the accuracy of the Ege’s test was equal to that of the JLT test and superior to that of the Mcmurray test. The Ege’s test was also more specific for both lateral and medial meniscus tears. So with the Ege’s test they were able to diagnose medial tears as accurate as with the JLT test, but with more specificity. (For the number crunchers amongst you, a lot of data in this study).

Karachalios T. et al (2005) tested 5 popularly used clinical tests to detect meniscus tears clinically for the medial and lateral meniscus (Mcmurray, Apley, JTL, Thessaly test at 5 degrees knee flexion, and the Thessaly test at 20 degrees of knee flexion). The Thessaly test at 20⁰ of flexion was 92% specific and 96 sensitive for lateral meniscus tears and 89% specific and 97% sensitive for medial meniscus tears. Only weak point in study was the lack of blinding of the clinicians and extensive exclusion criteria making it maybe a bit more difficult to use on the broader population. But based on the result, the Thessaly test at 20 degrees can be used as a tool to screen for lateral and medial meniscus tears.

Well, we are quite on a roll here checking out some studies about meniscus testing, a couple more? Here we go:

Scholten R. et al (2001) studied the accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing meniscal lesions of the knee with a Meta-Analysis. The inclusion criterion to for studies was at least one test for diagnosing meniscal injury compared with arthroscopy or MRI as gold standard. A lot of studies were excluded (check their inclusion criteria) so only 13 studies of the 402 studies found met the inclusion criteria. They concluded that there was little evidence that the diagnosis of meniscal lesions of the knee can be improved by applying the assessment of joint effusion test, the Mcmurray test, the joint tender line test, or the Apley compression test. They stated that the need for advanced diagnostic methods (e.g. MRI) or referral for surgical treatment can be based only on the severity of the patient’s complaints. An important part, for us physio’s, is read in their recommendations for the future. They say there is a need for research on diagnostic tests but in combination with patients history, patients characteristics, medical history…. This type of research may be more significant for use in a clinical setting.

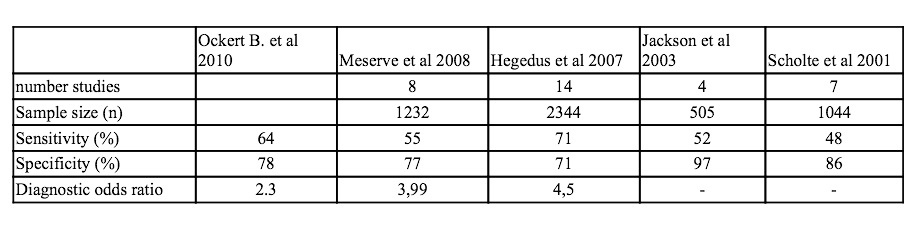

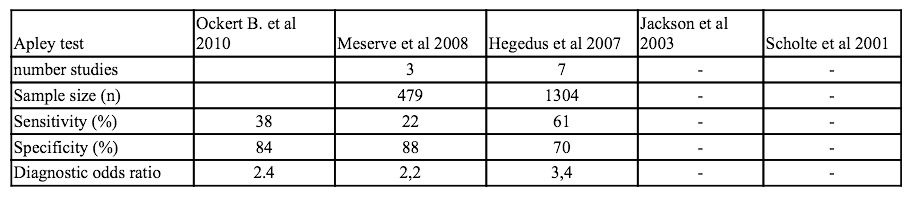

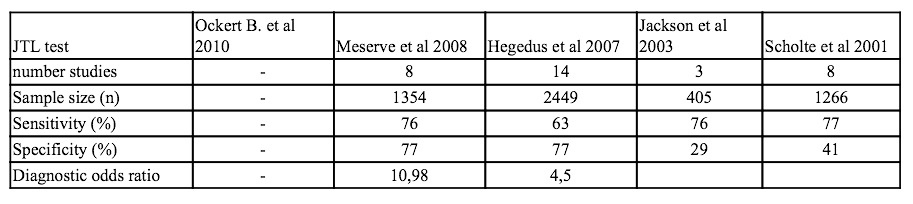

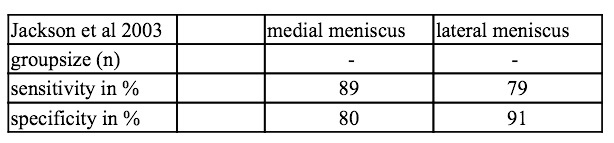

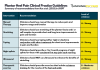

A couple of other meta-analyses were performed (Hegedus et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2003; Meserve et al., 2008; Solomon et al., 2001). To keep it a little easier to compare, I made a little table:

Results for the Mcmurray test:

Results for the joint line tenderness (JLT) test :

So in conclusion results of the meniscus tests are not that good. A lot of these studies test the accuracy, specificity, etc of one test to a golden standard (being arthroscopy or MR or both). This is of course the best statistical way of testing something. In that perspective we have to say that most of the tests designed to find meniscal tears are low to moderate. Except maybe for one test. We can assume that the Thessaly test offers an accurate and valuable tool for assessing meniscal tears in patients and it’s easy to perform (Karachalios T. et al 2005). But there is a but… Due to the weight loading of the test, it can be too aggressive to perform by the patient and increase symptoms like locking and pain. The Thessaly test at 5 degrees is safer than the one at 20 degrees but is less accurate and valuable. So what do we do with this? Is the meniscus test usable in practice?

Example video of Thessaly test;

Like I said before, a lot of these tests are compared with MRI or arthroscopy (gold standard in most studies). But that is not how we use all of these tests in the clinic, we normally use a couple of these tests in combination, to assess a patients knee. We also take in consideration the history of a patient (what he was doing at the moment of injury, were it hurts, can he localise the painful spot, what kind of pain does he have, is there swelling, inflammation. We can assess passive movement, are there restrictions, is there locking sensation, etc etc). An here lies our strong points as physios we don’t rely on a single test. There is a combination of tests, critical thinking and reasoning. Listening to the patients’ stories and putting the pieces of the puzzle together. So I am quite convinced that we can quite accurate test if a medial or lateral meniscus has been torn. The localisation and type of tear is lot more difficult to know (to know this for sure arthroscopy or MRI are needed). About the severity of the tear, we can make an educated guess based on the patients’ symptoms he/she presents with, and the reaction to therapy.

Ultrasound:

Ultrasound imaging (US) is not the best way to look for a meniscal tear because it cannot properly penetrate into the joint and visualise the cartilaginous injuries directly. So you have to look for secondary signs that may indicate underlying cartilage injury (i.e. meniscal cysts, who are commonly located on the lateral joint line and often communicate with some types of meniscal tears)(Holsebeeck MT. 2001). Azzoni R. et al (2002) also states that the use of US as the only imagining modality for diagnosing meniscal tears is unsatisfactory. I personally wouldn’t advise any of my patients to take an US.

MRI:

So what about MRI as a diagnostic tool in meniscal tears? I can hear you guys thinking, not again, not all these statistics all over. Well, good news, I’ll only give a few meta-analysis to see the effectiveness from MRI in diagnosing the meniscus.

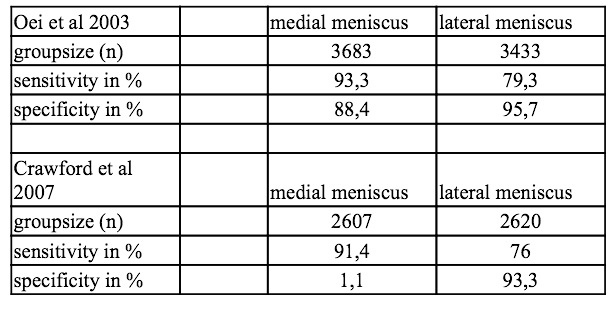

So off we go again…. (3 meta-analysis included) (all were compared with arthroscopy as gold standard)

So in conclusion for the MRI as a diagnostic tool to assess a meniscal tear we can be brief. There is very good sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing a meniscus injury. When we look at the numbers the results for the sensitivity of MRI for medial meniscus tears are better than those for the lateral meniscus. But MRI can be considered as a reliable tool in detecting meniscus injury.

Picture from Berthiaume et al. (2005) freely available here.

So with all this data under our belt, what should we do when a patient comes in to our practice with a possible meniscal tear?

Check the patients’ history. Gather as much info as possible on how the injury occurred, where it hurts, what are the patient movement restrictions and check signs and symptoms described above.

Do manual testing, combine different tests (accuracy and reliability is higher). I personally use the Thessaly test (when there is no real danger to locking the meniscus when the patient complains of a locking sensation, I don’t use this test) combined with JLT, Apley test and if necessary Mcmurray test.

If the pain of the patient is to severe and inhibits proper testing, or patient has a completely locked up knee in flexion or extension, I personally advise to get an MRI.

Arthroscopy should be the last intervention because it is an invasive technique.

As ever with any injury on RunningPhysio our site is not designed to replace medical advice, if in doubt get checked out!

_____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES:

1. Besette G.C. The meniscus. Orthopedics 1992;15:35-42.

2. Jee W.H. et al. Meniscal tear configurations: categorization with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180(1):93-97.

3. Magee T. et al. MR accuracy and arthroscopic incidence of meniscal radial tears. Skeletal Radiol 2002;31(12):686-689.

4. Tuckman G.A. et al. Radial tears of the menisci: MR findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;163(2):395-400.

5. Harper K.W. et al. Radial meniscal tears: significance, incidence and MR appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;185(6):1429-1434.

6. Helms C.A. The meniscus: recent advances in MR imaging of the knee. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;179(5):1115-1122.

7. Dorsay T.A. et al. Bucket-handle meniscal tears of the knee: sensitivity and specificity of MRI signs. Skeletal Radiol 2003;32(5):266-272.

8. Ververidis A.N. et al. Meniscal bucket handle tears: a retrospective study of arthroscopy and the relation to MRI. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006;14(4):343-349.

9. Ruff C. et al. MR imaging patterns of displaced meniscus injuries of the knee. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;170(1):63-67.

10. Brody J.M. et al. Lateral meniscus root tear and meniscus extrusion with anterior cruciate ligament tear. Radiology 2006;239(3):805-810.

11. Holsebeeck M.T. Sonography of large synovial joints. Musculoskeletal ultrasound. 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2001. pp.235-76.

12. Mohan et al. Reliability of clinical diagnosis in meniscal tears. Int. Orthop. 2007;31(1):57-60.

13. Rose R.E. et al. A comparison of accuracy between clinical examination and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of meniscal and anterior cruciate ligament tears. Arthroscopy 1996;12(4):398-405.

14. Akseki D. et al. A New Weight-Bearing Meniscal Test and a Comparison With Mcmurray’s Test and Joint Line Tenderness. Arthroscopy 2004;20(9):951-958.

15. Karachalios et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a new clinical test (the Thessaly test) for early detection of meniscal tears. J Bone Joint Surf Am 2005;87(5):955-962.

16. Scholten R. et al. The accuracy of physical diagnostic test for assessing meniscal lesions of the knee: a meta-analysis. J Fam Pract 2001;50(11):938-944.

17. Hegedus et al. Physical examination test for assessing a torn meniscus in the knee: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2007;37(9):541-550.

18. Jackson J.L. et al. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2003;139(7):575-588.

19.Meserve B.B. et al. A meta-analysis examining clinical test utilities for assessing meniscal injury. Clinical Rehabilitation 2008;22:143-161.

20. Solomon D.H. et al. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? Value of the physical examination. JAMA 2001;286(13):1610-1620.

21. Oei E.H. et al. MR imaging of the menisci and cruciate ligaments: a systematic review. Radiology 2003;226(3):837-848.

22. Crawford R. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus arthroscopy in the diagnosis of knee pathology, concentrating on meniscal lesions and ACL tears: a systematic review. Br Med Bull 2007;84:5-23.

Really good article, evidence-based and clear, I personally see few meniscal tears at the moment as most my patients are neurological, however I like to keep my sport / MSK eye in!

Many thanks for linking it to our CPD LinkUp too 😀

I have a small vertical radial tear of the lateral meniscus … sports chiropractor told me to go ahead with activities as tolerated — biking, running, yoga, etc — and that an orthopedic consult would be fine BUT he felt that they wouldn’t do anything.

Thoughts on continuing activities listed above???

Thank you … ARomaine

Comments are closed.