Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. For appointment options please see our clinic page.

I came across an interesting quote from a paper this week that got me thinking…

“Only 10% of the population has exactly equal lower limb lengths”

It was from this paper (Gordon and Davis 2019) which went on to say that approximately 90% of people have a leg length discrepancy of up to 1cm.

Now, delving into this a bit it seems this study is referencing earlier work by Knutson (2005) who reported that the average leg length difference was 5.2 mm and went on to say that for most people this difference doesn’t become clinically significant until it reaches approximately 2cm.

These figures got me pondering an interesting question – if only 10% of people have equal leg length, does that make symmetry abnormal?

I put this question out there on social media… it didn’t go well!!

There were lots of responses telling me I was wrong and that a difference as little as 3mm to 5mm could influence biomechanics, cause pain and ‘set people up for injury’. So I delved into this a bit more and here’s what I found…

A more recent paper (Vogt et al. 2020) gives a nice overview of the topic including these 5 top takeaways on Leg Length Discrepancy (LLD):

- It’s hard to accurately measure LLD in a clinical setting and reliably detect differences of less than 1cm.

- There may be a link between a LLD of more than 1cm and knee osteoarthritis but LLD was not found to be a factor that may lead to the development of back pain in a number of studies.

- LLD has a greater effect on double-leg stance activities (e.g. prolonged standing). The effect of LLD in single-leg stance activities is lessened as the gluteal muscles are able to stabilise the pelvis. [NOTE: running typically doesn’t include a double-leg stance phase].

- There is a lack of robust evidence to support the decision of when to initiate treatment and it shouldn’t be based solely on the magnitude of the LLD (i.e. how many centimetres it is).

- The treatment may be different in growing children compared to adults who have reached skeletal maturity (this paper mentions both).

Like many things in patient care this topic is nuanced. We can’t dismiss it altogether as irrelevant for all but likewise we need to be very cautious in assuming we can accurately identify a small LLD (e.g. less than 1cm) and that it’s relevant for someone’s pain.

The type of LLD is important too e.g. functional v structural and congenital v acquired (e.g. post surgery). Our bodies can adapt to our anatomy so we can manage a long-standing discrepancy. It’s unlikely that a patient’s anatomy has suddenly changed and explains new pain. However, with recently acquired LLD this represents a significant new change to biomechanics and may be more relevant.

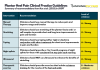

Vogt et al. (2020) provided this useful table to guide treatment:

A recent systematic review (Alfuth et al. 2021) concluded that the ‘block test’ may be the most valuable assessment method for LLD in clinic:

“The block test appears to be the most useful clinical assessment to measure LLD, followed by using devices, such as the pelvimeter. All other clinical tests seem to be not useful and may therefore be avoided by the clinicians and physiotherapists.”

What about runners?

Something that defines running is that during a run we don’t tend to have both feet on the ground at the same time. It’s rapidly moving from one single-leg stance to another with some flight time in-between. As a result, running is less likely to be influenced by leg length differences and research has reported that LLD was not associated with the development of running injury (Hespanol Junior et al. 2016 & Rauh et al. 2018). Rauh et al. (2018) was a study of 393 high school runners. They found that leg-length inequality was not associated with running injury, with the exception that male runners with a LLD of more than 1.5 cm were at greater likelihood of developing a lower leg injury (shin/calf). A tape measure was used to assess leg length which may have influenced accuracy.

Conclusion

It appears small leg length discrepancies of up to 1cm are very common and unlikely to be relevant to pain in many cases, especially in runners. A recent review from Applebaum et al. (2021) sums this up nicely:

“Length differences are typically less than 10 mm and asymptomatic or easily compensated for by the patient through self-lengthening or shortening of the lower extremities.”

However, LLD over 2cm are thought to alter biomechanics and loading patterns and may be associated with musculoskeletal disorders.

Differences of 1 to 2cm are perhaps a grey area. There is some evidence a LLD of 1cm can alter biomechanics so may be worth exploring if you think it’s relevant to pain. A small in-shoe raise is a simple thing to test to see if it helps symptoms or alters movement.

One final, important point… from the response to my post on social media, it’s clear there are still clinicians who believe our bodies can’t cope with a tiny amount of asymmetry. They suggested that even 5mm would have catastrophic effects through the foot and ankle, up the chain to the knee, hip and lower back. This is simply not the case! Most of you reading this will probably have a leg length difference of 5mm or more without even realising it! Let’s not scare our patients with these horror stories and make them lose trust in their bodies.

For more on running injuries, their assessment and treatment join us on the Running Repairs Course. We cover everything you need to get great results for runners in your care! Visit our course page to find out more and book your place.