Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. For more information see out Terms and Conditions.

I must admit I have a bit of a love-hate relationship with research.

I love how it can improve our practice and help us get better results with patients.

I hate how it’s often conflicting or limited by multiple flaws.

Recent guidelines for Plantar Heel Pain (PHP) highlight both sides of this story. They offer guidance on what treatments to consider in practice but the two guidelines vary significantly in their recommendations.

It’s interesting how two experienced research groups can look at the same evidence and reach quite different conclusions. The authors of the 2021 guide (Morrissey et al. 2021) actually wrote to the editor-in-chief of the JOSPT to challenge some of the findings of the later guide (Koc et al. 2023).

We can see there is some disagreement on exactly what ‘best practice’ is so let’s have a brief look at both guidelines, starting with the most recent:

Koc et al. (2023) best practice guide published in JOSPT:

This Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) is a revision of the 2014 CPG and identified 64 meta-analyses and 126 systematic reviews that have been published after the search date for the previous CPG.

Our graphic below provides a brief summary of their recommendations. As ever, the devil is in the details, so I’d recommend seeing the full guidance for more information.

One thing I would like to point out is that these are not my recommendations! I’m just sharing the words of the CPG. It’s also worth noting the strong recommendation NOT to use ultrasound.

This is clearly a substantial piece of work that shouldn’t be dismissed, but there are several criticisms that have been raised:

- There’s a larger focus on ‘hands-on’ treatments such as manual therapy and low-level laser, with less information on education and load management, which are often key in PHP.

- Some treatments, such as shockwave, were not included as they were considered outside of the typical scope of practice.

- Questions have been raised over the quality of the evidence behind some recommendations.

- The guidance tells clinicians what to include/ exclude rather than focusing on the strength of the evidence and making a shared decision with the patient. For example, they say, ‘Clinicians should use manual therapy. ’

- The previous best practice guide in the BJSM wasn’t included

For more on this, I recommend reading the letter to the editor-in-chief of JOSPT and response from the 2023 CPG authors.

Morrissey et al. (2021) best practice guide, published in BJSM:

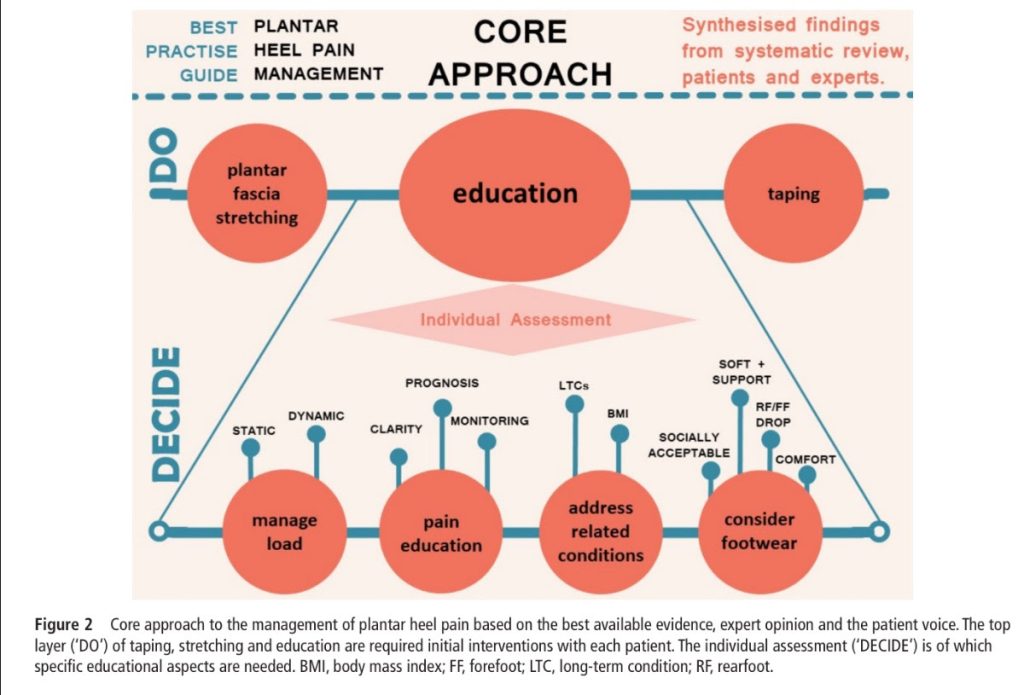

This guidance was developed based on a synthesis of a systematic review integrated with expert clinical reasoning and patient values.

It focuses more on individual assessment and “management, which consists of the simple but active, supported self-management interventions”

This graphic below summarises their ‘core approach’:

Image Source: Morrissey et al. (2021) BJSM *Open Access*

This guidance is much more in line with how I would manage PHP. The quote below provides a nice, brief summary of their recommendations:

In terms of ‘individual education’ Morrissey et al. (2021) mention several areas to consider:

- Load management to break up provocative loading and/ or ensure sport and activity is at a manageable level

- Improving understanding of pain and how it may be used to guide activity (e.g. a traffic light approach based on pain score )

- Footwear advice to ensure comfort (such as wearing a shoe with a heel-to-toe drop that helps symptoms)

- Support to address comorbidities (such as Type 2 Diabetes)

A surprise exclusion?!…

You may notice that progressive strength training features less in these recommendations. That might go against our biases (especially when working with runners) but it’s understandable when you consider that there aren’t currently a lot of studies of it in PHP at present. I believe it has value, particularly in sporty and active individuals but we don’t have a lot of evidence to support that yet.

For more on exercise options for heel pain, see our article on rehab programmes for PHP.