Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. For more information see our Terms and Conditions.

Running Repairs covers all common running injuries including Patellofemoral Pain (PFP), which is a nice segue to today’s topic…

Exercise seems to help PFP and many conditions but the truth is we’re not entirely sure why or if it needs to be specific to certain area. For example, there’s some evidence (Smith et al. 2017) that wall squats may help neck pain!

We often think it’s addressing the physical impairments that leads to improvement in symptoms. That may well be the case but it isn’t necessarily what the evidence always shows. For example, Hott et al. (2019a) observed that pain and function improvements may not be directly tied to gains in muscle strength in patients with PFP.

As we discussed in last week’s newsletter, quads and gluteal strengthening are commonly advocated in PFP but there is some evidence that may question their superiority. So in today’s email we’ll explore that and look at how we might integrate other areas into PFP rehab.

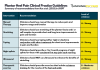

First up an intriguing study from Almeida et al. (2021) on 52 women with PFP. They compared two exercise approaches:

- Hip Adduction in side-lying

- Flex ring squeeze side-lying

- Hip internal rotation with elastic resistance

- Hip Abduction in side-lying

- Claim with elastic resistance

- Hip external rotation with elastic resistance

Both groups completed a warm-up of cycling and stretches and the knee exercises consisted of seated knee extensions and squatting. Now, we might expect that the posterolateral exercises would target the glutes and be of more benefit but that’s not what the study found:

An important consideration of this study is that both groups received knee strengthening so we’re not comparing these different approaches in isolation. This is likely because of the evidence to support knee targeted exercises.

Other studies have shared a similar approach. Kisacik et al. (2021) found that adding ’short foot exercises’ to knee exercises improved outcomes in a subgroup of patients with PFP and ‘weak and pronated’ feet. Mølgaard et al. (2018) also found that the addition of foot-targeted exercises and orthoses was more effective than knee-targeted exercises alone for individuals with PFP.

So there does seem to be some evidence to support targeting the foot and ankle alongside the knee but what about the foot in isolation?

A large study in India compared Tibialis Posterior strengthening with Quadriceps strengthening in 170 people with Anterior Knee Pain and ‘flat feet’ (Kavi priya et al. 2024). Their findings were surprising…

**Now, a word of caution. I’m providing a quick overview here, I’d recommend looking at the studies themselves as there will be limitations to consider.**

For example, in Kavi priya et al. (2024) is publish in a low quality journal and has multiple limitations. The knee exercises are very low-level isometric options with no mention of load progression. Old school stuff like inner range quads work and static straight leg raises. They also used a convenience sampling method, rather than randomisation. Footprint analysis was used to categorise feet as ‘flat’ which can have issues with accuracy and reliability.

It does appear that there may be benefits from targeting the hip, knee or foot and ankle (or a combination) in people with PFP. However, the findings of Hott et al. (2019a) challenge whether targeting the hip or knee are superior to ‘free training’:

The ‘free training’ group in this study was encouraged to be physically active in accordance with standardized information. All 3 groups received education about PFP. The knee-targeted exercises were somewhat old school (similar to the study above) but could be progressed with weight/ resistance tubing. A long-term follow-up study of these 3 groups also revealed no difference in results at 1 year (Hott et al. 2019b).

It may be that other factors beyond strength gains influence exercise outcomes in PFP, including psychological benefits and Exercise-Induced Hypoalgesia (EIH). Most types of exercise can potentially reduce pain but it seems there is significant individual variation as discussed by the excellent work in EIH by Naugle et al. (2013).

Let’s come back to the original question – does exercise selection matter in PFP? On balance, my answer is yes, but finding an option that suits your patient may be as important as targeting a specific area.

This is often a priority for patients with very irritable symptoms who can’t tolerate loading the knee. In these cases, I might look for NPGs – Non Painful Gains. Here are some exercise examples that could help a patient while remaining unlikely to aggravate due to low load at the knee:

- Side-lying hip abduction

- Hip internal/ external rotation strengthening with band

- Bridge/single-leg bridge

- Straight leg calf raises

- Short foot exercises and band work (e.g. resisted inversion)

- A non-provocative goal activity (e.g. walking, cycling, swimming etc)

As with any treatment option, they need to be considered on an individual basis and tested to see how symptoms respond. We still want to recognise that the current best practice guide recommends knee-targeted exercises so these will often be a priority when the patient can tolerate them but they’re far from the only option!

I think that’s my main takeaway from these studies – target the knee where possible but consider the hip, foot and ankle as well as more general options for exercise and activity.